Originally published in the Daily Hampshire Gazette on Feb. 2, 2021

By Steve Pfarrer

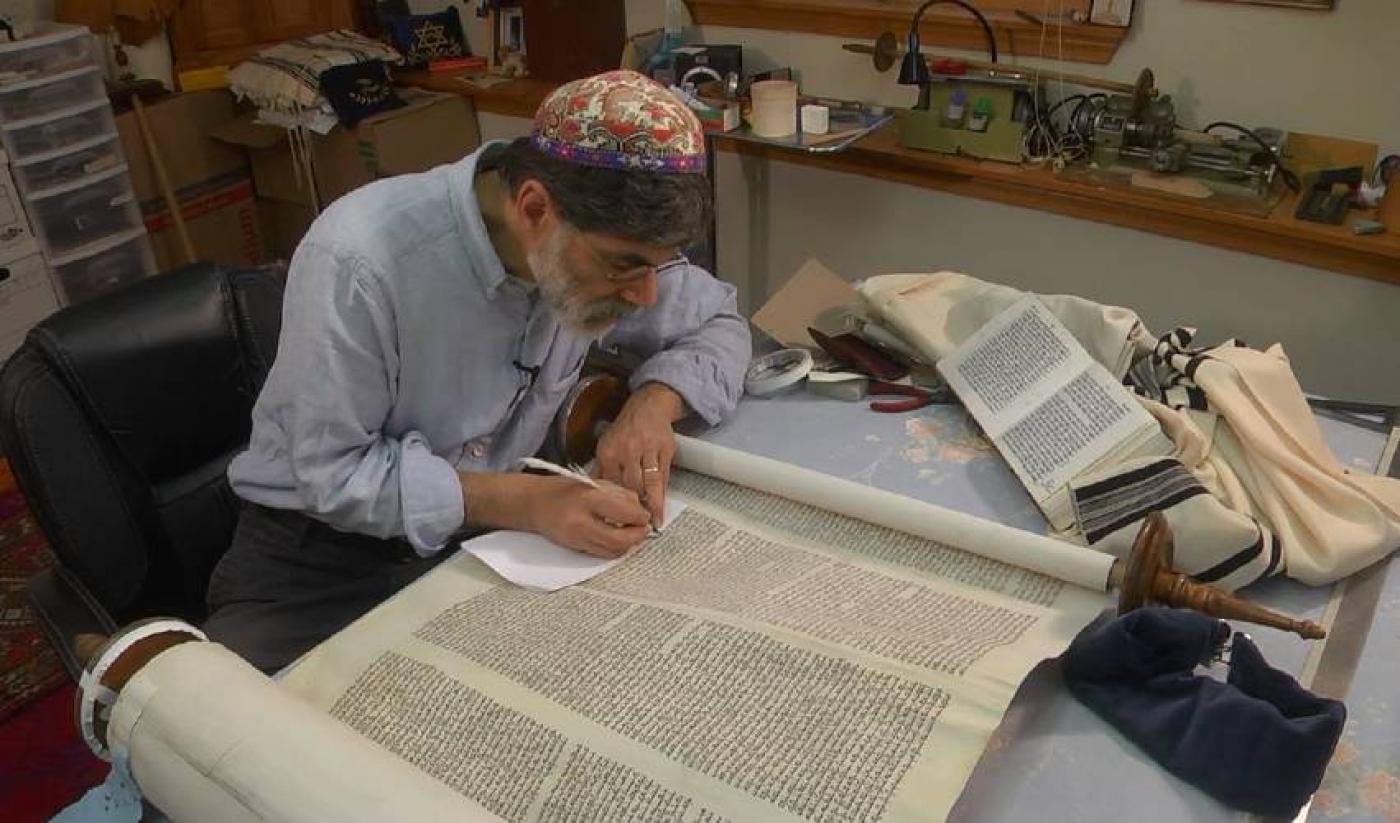

Northampton Rabbi Kevin Hale, a sofer, or Torah scribe, works on a scroll in his Leeds office in a scene from “Commandement 613.”

Last March, the Pioneer Valley Jewish Film Festival (PVJFF), a staple in the region since the early 2000s, was just about to present its latest edition, with some 15 films and a number of related events poised to take place in about a dozen venues up and down the Connecticut River.

Then the pandemic arrived — and that was it for the 2020 version of the film fest, with all events canceled.

But the film festival, produced by the Springfield Jewish Community Center, is now returning in a virtual format, with seven films showing from Feb. 6 to March 22. Each week during that span, one of the films will be available for free online viewing for up to 48 hours by registering at the PVJFF website (pvjff.org); donations to the film fest are encouraged and can be made when you register.

On tap are a range of films — a historical drama, a profile of Israeli wildlife photographer Amos Nachoum, a look at how the popular musical “Fiddler on the Roof” came to be made — as well as a short documentary with a local and historical twist. “Commandment 613” offers a look at how Northampton Rabbi Kevin Hale, a sofer or religious scribe, restores Torahs that can be hundreds of years old, including many saved from destruction in Europe during World War II.

Deb Krivoy, the festival director, says most of the films will be followed by Zoom-based discussions featuring directors, screenwriters, local scholars and special guests. Larry Hott, the longtime documentary maker with Florentine Films/Hott Films in Florence, will moderate some of those discussions.

Though fewer films are being offered virtually than at the past live festivals, Krivoy said the online format will allow more people to view those movies, and to do in the safety of their homes. Most of the films on tap for 2021 had been scheduled to screen last year, she noted.

Among the highlights are “It Must Schwing!: The Blue Note Story,” a look at how Alfred Lion and Francis Wolff, two young Berlin émigrés, founded the legendary jazz label Blue Note Records in New York in 1939, which became a platform for storied African-American players such as Miles Davis, Herbie Hancock, John Coltrane, Sonny Rollins, and Thelonious Monk.

There’s also “The Keeper,” a 2018 historical drama about Bert Trautmann, a German POW in Great Britain following World War II who became a star goaltender for a leading soccer team in Manchester, England, despite initial opposition from many fans, including in Manchester’s Jewish community. The story features a lead performance by David Kross (“The Reader, “War Horse”) in what one critic calls “a magnificent epic [that] speaks to the power of sports to unite.”

Treasures in Judaism

“Commandment 613,” which will screen March 5-8, is named after the final commandment in the Torah — the first five books of the Hebrew Bible — which is to write such a scroll for yourself.

The film follows the work that Hale, the Northampton rabbi, does to restore two Torahs that were among nearly 1,600 scrolls saved in Prague, capital of what was then Czechoslovakia, after World War II. Workers in a Jewish museum in the city had stored Torahs and other valuables from synagogues that had been shut down following the German occupation.

The scrolls were brought to England in the 1960s, and some have since been preserved in a museum there, while the majority have been donated to Jewish congregations around the world.

The film’s director and producer, Miriam Lewin, who lives in Brooklyn, New York, is a first cousin of Hale; she knew something of his work as a sofer and had herself grown up Jewish. But until about 10 years ago, Lewin said during a recent phone interview, she had never seen a Torah up close.

Then, while attending the bat mitzvah of a stepdaughter with Hale, she looked on as her cousin, during a delay in the ceremony, held an impromptu information session for guests about the Torah being used there.

“I watched as people clustered around it, and the looks on their faces as Kevin talked about it told me there was something really special happening,” Lewin said.

That prompted her to work with Hale on “Commandment 613” along with her editor and principal camera operator, Randi Cecchine, a Hampshire College graduate who has worked with Lewin on previous documentaries. They filmed Hale at his studio in Leeds and also in two Pennsylvania locales — a synagogue and a retirement home for Jewish residents — where he was called in to repair aging Torahs.

Hale, originally from Long Island in New York state, was the first hired rabbi for Beit Ahavah, a Reform Jewish community in Florence that was started in the late 1990s. As a sofer or Torah scribe, he uses traditional tools, such as quill pens, to rewrite faded letters in Torahs. Among other tasks, he’ll also sew up the ripped parchment Torahs are made of by using fiber created from the same kind of animal used to make the parchment.

As he explains in the film, Hale grew up somewhat ambivalent about Judaism, dropping out of attending synagogue before he would have had his bar mitzvah, studying classics in college, then becoming a toymaker. But he was later drawn back to the faith, first to become a rabbi, then to train as a sofer.

“I sensed there were treasures in Judaism, and I wanted to find them,” he tells the filmmakers.

In a phone interview, Hale said his father, who escaped Germany with his family in 1939, had trained as a cabinetmaker before leaving the country “and some pieces of that have stayed with me, the practice of craftsmanship.” He also said he was gradually drawn back to investigate Judaism by examining the history of Nazi Germany and the experience his father’s family had there.

“What is it about Judaism that made them want to kill us?” he said. “I picked at that for a couple of decades.”

That led him in turn to look at the Torah more closely and think about what it meant. In “Commandment 613,” he and others interviewed make the point that Torahs, many of them hundreds of years old, are living documents, written by hand following rules and techniques that themselves go back thousands of years. In that sense, they are repositories of a community’s memories, history and hopes, and they’re central to Jewish rituals.

Working on them, then, is about more than just making repairs, Hale says. It’s about paying tribute to the past and connecting him to God — as well as to the scribe who first wrote a particular Torah.

Richard Remenick, chair of a committee for the Pennsylvania synagogue that hires Hale to repair its Torah, likens the historic scroll, created 200 to 250 years ago in what is now the Czech Republic, to a living being.

“When I first found out about this project,” Remenick says in the film, “I said ‘Think of the Torah as a person, and how it would feel if it could not tell its story. If it were neglected, it would be like a second death.’”

One scene toward the end of the film shows members of the Pennsylvania synagogue clustered around the restored Torah after Hale has finished his work, with some taking turns reading from it; there’s clearly a spirit of celebration at hand.

And Hale sums up his work like this: “It’s very healing to restore Torahs that were really slated for destruction.”

Hale, Lewin and Cecchine will host a Zoom discussion following the film.